Bolivia: The Chaco, Valle Zone, and Central Andes

-

Sep 23 to Oct 7 2026

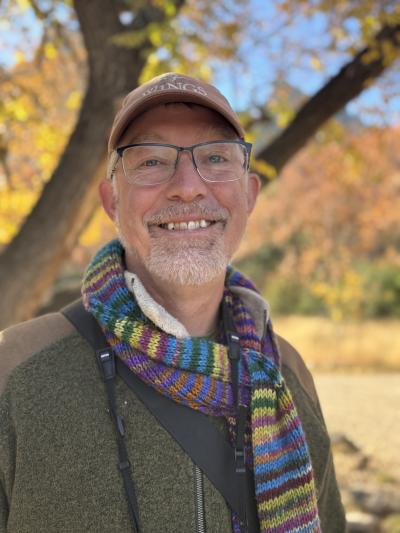

Rich Hoyer

2026

Single Room Supplement $170

2026

Single Room Supplement $170

With high mountains and plains dominating the west, the Amazonian Basin in the north, the Pantanal wetlands in the far-east, and the Chaco in the south, the large country of Bolivia contains more diverse biomes than any other on the bird continent, making it also the birdiest landlocked country in the world. A native woodland type—the Chiquitania—and isolated interior dry valleys add to the diversity, even harboring some endemics and many other species not seen so easily anywhere else.

The stereotype of Bolivian political instability is long outdated, but the country is still mentioned only infrequently in the mainstream media and tourism literature, keeping it off most birders’ radar. Those who have been there, however, rave about Bolivia’s unparalleled biological diversity, long list of exciting birds, relative ease of travel, and friendly people. With a low population density, Bolivia offers roadside birding as good as it gets. Our eight tours here in recent years have amassed a total of over 900 species, and while no tour of moderate length can sample all the habitats, we visit a surprising variety, taking in some of Bolivia’s most famous sights along the way.

This tour can be taken in conjunction with our Bolivia: Northern Andes, Madidi National Park, and Barba Azul tour.

Day 1: The tour begins this evening in Santa Cruz. Night in Santa Cruz.

Day 2: Our first day of birding will be on the outskirts of town, in a reserve of mixed grasslands and semi-deciduous forest. The entrance drive may yield Red-winged Tinamou and perhaps even Red-legged Seriema and Greater Rhea, some of the most spectacular birds of South America. We’ll check the area for such interesting species as Small-billed Tinamou, Whistling Heron, the long-tailed and colorful Chotoy Spinetail, the furtive Fulvous-crowned Scrub-Tyrant, and Grassland Sparrow. Night in Santa Cruz.

Day 3: We’ll leave early this morning for the drive south to new habitats. Thanks to the newly paved highway connecting Bolivia to Argentina, the drive to the Bolivian Chaco is not as arduous as it just 15 years ago, and we’ll have time for roadside stops. We’ll pass through a range of habitat transitions: the tall, dry forests are home to the near-endemic Bolivian Slaty-Antshrike and the loud and strikingly colored Striped-backed Antbird, while the more humid Andean foothill woodlands are inhabited by Blue-fronted Parrot, lively Green-cheeked Parakeets, and Plush-crested Jay. Night in Camiri.

Days 4–5: Bolivia shares with Paraguay and Argentina the “Chaco,” a mix of thorn forest, scrub, and savanna habitats that support several endemic species. We’ll spend all of one day driving roads through this area, stopping whenever we see activity, and we’re certain to find many species not possible anywhere else on the tour. One of the primary targets is Black-legged Seriema, seen more easily on this tour than on any other. Other characteristic birds include the well-named Many-colored Chaco-Finch, the delightful Lark-like Brushrunner, and the jay-like Brown Cacholote. The Crested Hornero, a clever variation on the ubiquitous Rufous Hornero, is scarcer but certainly possible, as are the subtle Cinereous Tyrant, secretive Crested Gallito, and vocal Chaco Earthcreeper. White-barred Piculet and Checkered Woodpecker are even more likely, and we can always hope for Black-bodied Woodpecker, here just at the edge of its range.

On our other day we’ll change directions and bird some foothill woodlands not far from town. The brushy roadsides along the way will be teeming with flocks of Black-capped Warbling-Finches, Red-crested Finches, Red-crested Cardinals, and Golden-billed Saltators. Closer inspection of denser vegetation could yield skulking Ochre-faced Tody-Flycatcher and Moss-backed Sparrow, and we’ll need to keep our heads up to catch sight of Yungas Guan and Ocellated Piculet, one of three species of piculet possible on this tour. We’ll pass through the historic village of Lagunillas on the way to a series of wetlands where we could see Comb Duck, Ringed and Brazilian Teals, Spot-flanked Gallinule, and Southern Screamer. Even though we’re still in the lowlands, the nearby cliffs of the outermost Andean foothills are home to Andean Condor, the very rare and local Military Macaw, and Solitary Eagle. In short, it should be a bird-packed day.

Interesting animals and other creatures could enliven our days here. The Chaco is known for its armadillo diversity, with Big Hairy Armadillo being a distinct possibility. If it hasn’t been too dry, a number of interesting semi-temperate metalmarks and hairstreaks could be around, and on one of our tours here we discovered a most beautiful widow spider, Latrodectus corallinus, previously known only from Argentina. By late-afternoon on both days we’ll return to our hotel. Nights in Camiri.

Day 6: It’s a long drive to our next destination, broken by stops for some brief birding and lunch. A pause at Laguna Tatarenda could result in Black-necked Stilts (the southern form with a white back, which actually may be a different species), migrant Wilson’s Phalaropes and Lesser Yellowlegs, and perhaps other waterbirds. White Woodpecker, Burrowing Owl, and White Monjita are some birds by the roadside that may cause us to stop from time to time. By late-afternoon we’ll arrive at the gate of our home for the next two nights. Night at Refugio Los Volcanes.

Day 7: Refugio Los Volcanes, a privately owned nature preserve, is in an idyllic, isolated valley on the edge of Amboró National Park. We’ll spend a full day here birding the preserve’s trails. One trail crosses a meandering, rocky stream through the forest, where White-throated Piping-Guan and Sunbittern are often seen. Gray-throated Leaftosser may be found working the leaf litter, and colorful Blue-naped Chlorophonias are possible in fruiting trees. Another trail takes us to a scenic waterfall and deep swimming hole, while a third leads up a narrow canyon that almost always has some active feeding flocks. Bolivian Recurvebill, a rare and unusual near-endemic, has been sighted here, and flocks along this trail can include Buff-fronted Foliage-gleaner, Ocellated and Black-banded Woodcreepers, Black-capped Antwren, Marble-faced Bristle-Tyrant, and Black-goggled Tanager. We’ll also bird the entrance road, where the very attractive Chestnut-backed Antshrike, White-winged Tanager, White-bellied Pygmy-Tyrant, and elusive Slaty Gnateater can sometimes be found. If we’re very lucky, we’ll see the secretive Rufous-breasted Wood-Quail, Short-tailed Antthrush, or Gray Tinamou.

Time spent relaxing around the refuge buildings can also be productive. A fruiting tree at the edge of the clearing could host a bonanza of species such as Cinereous Conebill, Blue-browed Tanager, and Pale-vented Pigeon (or maybe a troop of Brown Capuchins), and we’ll keep a watchful eye on the sky in the late morning for Andean Condor, Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle, Black-and-white Hawk-Eagle, or even Solitary Eagle. Channel-billed Toucan and Bat Falcon perch on exposed snags, and noisy flocks of Mitred Parakeets are commonplace.

The flora here is spectacular, and we’ll likely see several species of blooming orchid, the lady-slipper Phragmipedium caricinum, growing like grass on the stream boulders being one of the more attractive ones. Thanks to the humidity, we’ll notice a big uptick in the butterfly numbers here (the many species of clearwings are particularly noticeable), and the permanent stream will give us a chance to photograph a few damselflies and dragonflies as well.

Since we’re located in the middle of prime birding habitat, some night birding will be possible. On a private tour here we discovered that the long-presumed Spectacled Owls near the rooms were in fact the much rarer Band-bellied Owl, while Ocellated Poorwill is here at the southern edge of its range. Night at Refugio Los Volcanes.

Day 8: We’ll have the first hours of the day to bird the entrance road of Refugio Los Volcanes before we continue to lunch in the historic town of Samaipata. After lunch we’ll continue to our next destination, and we’ll find the changing landscapes and plant life fascinating – several species of endemic cactus grow by the roadsides, trees become covered in several species of epiphytic bromeliads, and spiny thickets are formed by terrestrial bromeliads (many also endemic). We’ll be tempted to make at least a stop or two, perhaps finding our first Gray-crested Finches or Glittering-bellied Emerald along the way. Night in Comarapa.

Days 9–10: One full day in the Valle Zone and another in the nearby cloud forest of Siberia should give us plenty of time to pry out most of the wonderful birds found in this uniquely Bolivian ecoregion, a series of north-south valleys protected by the Andes from Amazonian weather systems. This zone is much like the deciduous thorn forests of Mexico, but the species makeup is very different here. Pepper trees, familiar as a landscaping plant in Arizona and California, are native here, as are many species of giant columnar cacti—but the birds that inhabit this area are wildly different from anything found in North America. The most spectacular endemic is the Red-fronted Macaw, and finding it will be a priority for us. Also endemic to this region are the Cliff Parakeet (quite different from, yet still considered conspecific with, the more southerly Monk Parakeet), Bolivian Blackbird, and Bolivian Earthcreeper.

Above the town of Comarapa is a patch of cloud forest in the Serranía de Siberia—though it is never really as cold as its namesake. Here the endemic Rufous-faced Antpitta is quite common (though never easy to see), and other forest inhabitants include Andean Guan, Black-winged Parrot, Violet-throated Starfrontlet, Strong-billed Woodcreeper, Golden-headed Quetzal, Maroon-belted Chat-Tyrant, Buff-banded Tyrannulet, Pale-footed Swallow, Pale-legged Warbler, and the endemic Gray-bellied Flowerpiercer.

The semihumid transition zone between the cloud forest and the drier valleys is where the lovely warbling-finches reach the peak of their diversity. Ringed Warbling-Finches can be common in roadside flocks, while finding Black-and-chestnuts and Rusty-browed may take a little more effort. Bolivian Warbling-Finch is also a possibility here, and we’ll make an effort for Spot-breasted Thornbird and Giant Antshrike. The beautiful Olive-crowned Crescentchest (now in a tiny family with just three other species) is yet another of our targets here, while Cream-backed Woodpecker, a large crested woodpecker, will be a lucky find. Nights in Comarapa.

Day 11: We’ll have one last morning in the Siberia cloud forests before continuing westward and up and down rain-shadowed valleys, mostly in the lee side of the outer Andean ridge. Hooded Siskin, Purple-throated Euphonia, and Blue-and-yellow Tanager are sometimes common roadside birds, while patches of Polylepis might have the very local Thick-billed Siskin, skulking Bolivian Antpitta, or Black-hooded Sunbeam. After our longest drive on a now mostly-paved road we’ll arrive at our hotel in Cochabamba. Night in Cochabamba.

Days 12–13: The Cochabamba Valley, one of Bolivia’s population centers, is at the nexus of three habitats: the dry interior Valle Zone reaches its highest elevation here, merging with the open puna of the high Andes, while the influence of the wet cloud forests of the Amazonian slope seeps over into local canyons. As a result, our next three days will bring an interesting change in habitat and birdlife as we explore these higher and drier woodlands, semihumid scrub, tundra-like habitat, and moist treeline cloud forest. Polylepis patches and woodland on the road up Cerro Tunari, the small range of rugged, towering peaks north of town, is home to the Cochabamba Mountain-Finch, which occupies one of the narrowest ranges of any of Bolivia’s endemics. The lovely and petite Gray-headed Parakeet forages in roadside weeds like a sparrow, the spectacular Red-tailed Comet is relatively common at blooming shrubs, and the nearly endemic Wedge-tailed Hillstar is a possibility. On the drier slopes we’ll search for birds such as Brown-backed Mockingbird, Plain-breasted Earthcreeper, Andean Swift, Creamy-breasted Canastero, Plain-mantled Tit-Spinetail, and Andean Hillstar (the endemic subspecies), among many others. The rushing stream below often has Torrent Duck.

Roadside birding at the highest elevations may reveal several species of furnariid, such as Slender-billed Miner and Cordilleran Canastero, foraging among the boulders and grass tufts, while many kinds of ground-tyrants, such as Cinnamon-bellied, Rufous-naped, Taczanowski’s, Ochre-naped, and Cinereous, are possible on the grassy flats. Additional birds of interest include the subtle Glacier Finch, the simple yet enigmatic Boulder Finch (usually requiring a hike), and Black-winged Ground-Dove.

If it remains sunny into the warmer afternoon at the highest elevations (for it often fogs over), there are some little-known butterflies – skippers, satyrs, hairstreaks, and yellows – that will become active and visit the tiny cushion flowers in the tundra. Nights in Cochabamba.

An earlier start on another day will be in order as we head for the cloud forests on the Chapare Road. Right at treeline is a moist, densely vegetated canyon where the birding can be very exciting. Yungas Pygmy-Owl is a good possibility here, while Scarlet-bellied Mountain-Tanager, Three-striped Hemispingus, and Spectacled Redstart populate the hyperactive mixed flocks; other specialties include the endemic Black-throated Thistletail, Light-crowned Spinetail, Crowned Chat-Tyrant, and Stripe-faced Wood-Quail. Brown-backed Chat-Tyrant and Puna Tapaculo are common where the last shrubs meet the higher grasslands, while Trilling Tapaculo can be commonly heard in the undergrowth just below there. Bolivian Tyrannulet, Deep-blue Flowerpiercer, and Scaly-naped Parrot are seen regularly at slightly lower elevations, while the rare but distinctly possible Hooded Mountain-Toucan and Chestnut-crested Cotinga are a couple of the most-sought after birds as well. Among the many hummingbirds here are the Amethyst-throated Sunangel, Great Sapphirewing, and Tyrian Metaltail, and one of the most spectacular hummingbirds, the endemic Black-hooded Sunbeam, will be our primary target.

Day 14: We’ll have a last day to bird wetland habitats in the valley around Cochabamba, in search of Wren-like Rushbird and Many-colored Rush-Tyrant in the cattails, while open water may harbor Speckled and Puna Teals, Yellow-billed Pintail, Rosy-billed Pochard, Andean Duck, and Silvery Grebe. White-tipped Plantcutter is common in the scrub around lakes. For those that are only doing this tour you will take the 45-minute evening flight back to Santa Cruz and overnight there.*

Day 15: The tour ends this morning with transfers to the international airport.

Note: The information presented here is an abbreviated version of our formal General Information for Tours to Bolivia. Its purpose is solely to give readers a sense of what might be involved if they took this tour. Although we do our best to make sure what follows here is completely accurate, it should not be used as a replacement for the formal document which will be sent to all tour registrants, and whose contents supersedes any information contained here.

ENTERING AND LEAVING BOLIVIA: A passport valid for at least six months after the date of your arrival and with at least one blank page for an entry stamp, and a visa are required for U.S. citizens traveling to Bolivia for any purpose. Citizens of other countries should contact their nearest Bolivia Embassy or Consulate.

Bolivia requires proof of Yellow Fever Vaccination upon application for a visa and arrival into the country.

For more information, visit the Bolivian consulate web site at http://www.boliviawdc.org/consulate/visas/tv.

COUNTRY INFORMATION: You can review the U.S. Department of State Country Specific Travel Information here: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel.html and the CIA World Factbook here: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/. Review foreign travel advice from the UK government here: https://www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice and travel advice and advisories from the Government of Canada here: https://travel.gc.ca/travelling/advisories.

PACE OF THE TOUR: Early mornings and full birding days will be the rule, but we always try to be back at the hotel well before dark and allow at least hour off before dinner. Sunrise is around 6:00 a.m., so daily departures from the hotel are usually around 4:30 to 5:30, depending on the length of the drive, and we are back to the hotel by about 4:30 to 5:00. The pace is considerably more relaxed during our day at Refugio Los Volcanes, as there will be no driving.

During most of the tour, birding will be on dirt or paved roadsides, but at Refugio Los Volcanes we’ll be on trails and the main entrance road. The road itself is very steep in places with loose gravel, and footing can be difficult. Some of the trails are very flat and easy, but many are also narrow, quite steep in places, and they may have washed-out or rock-covered sections. We’ll have to rock hop across a stream in several places if the plank bridges are out, and a stroll down the stream one afternoon might include some patches of knee-deep quicksand that one will have to pay attention to avoid. The farthest we walk from the lodge is less than a mile each way, often much less. Walking sticks are highly recommended.

In the areas of highest elevation at Cerro Tunari we’ll spend a short period walking off the road on the tundra-like vegetation, and in some areas we may wander opportunistically up rock-strewn washes with very uneven footing. We may spend about an hour to look for Short-tailed Finch up to a ¾ kilometer away but within sight of the vehicle. We’ll have to traverse a 50-meter section of large boulders and hop on rocks over a stream; this requires a fair amount of agility. During the occasional difficult hikes like this, one can stay with the vehicle.

Throughout the tour we do lots of standing and watching, and we generally move very slowly. If this tends to tire your lower back a small, lightweight travel stool that you can carry with a strap over your shoulder would be useful.

HEALTH: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all travelers be up to date on routine vaccinations. These include measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine, varicella (chickenpox) vaccine, polio vaccine, and your yearly flu shot.

They further recommend that most travelers have protection against Hepatitis A and Typhoid.

The most current information about travelers’ health recommendations can be found on the CDC’s Travel Health website here: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/list

Malaria: Malaria is very rare where we are. Please consult your physician as to the advisability of taking a prophylaxis.

Please contact your doctor well in advance of your tour’s departure as some medications must be initiated weeks before the period of possible exposure.

Leishmaniasis: Tiny phlebotomine flies (technically called sand flies but not related to the gnats that bite in sandy areas) carrying the Leishmania parasite do exist at lower elevations in Bolivia, but the risk is not high, as we rarely see the insect, and not all are vectors. If the insect is seen (it looks like a tiny, pale mosquito and is active only from dawn to dusk), the leader will point it out; steps to avoid exposure are the same as for mosquitoes.

Elevation: We will be going as high as 14,800 feet (4500 meters) on at least one day. Although we will do only a bit of walking here, some will be on a surface resembling a stony golf course down at about 13,750 feet (4200 meters). Some people experience just lightheadedness and a need to take deeper breaths with only a little exertion; some just find it exhilarating. But many experience a delayed effect of nausea and headache, which can be mitigated by drinking plenty of water, and which will eventually disappear after several hours. Acetazolamide is an effective drug that alleviates side effects of high elevation. While this is a prescription drug in the United States (Diamox), it can be purchased over the counter in Bolivia, and we’ll be making a stop at a drugstore to obtain some during the tour. Please consult your doctor if you think high elevation may be an issue for you.

Insects: Mosquitoes will generally not be problem as we are here during the end of the dry season, but there may be small biting gnats, especially in the cloud forest and at Refugio Los Volcanes when it is sunny. Refugio is a transition zone to Amazonian foothill forest, so mosquitoes or sand flies could be here in the evening, and one should be protected. The best defense against any insects is to wear long-sleeved shirts and pants, especially in the evenings and to use repellent on exposed skin. Roadside vegetation may harbor chiggers in the lower elevations, and we’ll do our best to avoid them.

Smoking: Smoking is prohibited in the vehicles or when the group is gathered for meals, checklists, etc. If you are sharing a room with a nonsmoker, please do not smoke in the room. If you smoke in the field, do so well away and downwind from the group. If any location where the group is gathered has a stricter policy than the WINGS policy, that stricter policy will prevail.

Miscellany: One can never completely escape the risk of parasites or fungal infections. Please consult with your physician. We avoid tap water; filtered and bottled water are readily available.

Sun and UV exposure in the higher elevations can be very intense. Please bring adequate protection, including a sun hat and a strong sun screen of at least 15 rating.

Snakes of any kind are rarely encountered in the tropics, and we will be lucky to see one. Furthermore, venomous species are in the minority in the Americas, and we spend very little time on trails in the humid lowlands where one would have the greatest chance of finding one.

CLIMATE: Since we will be nearing the end of the dry season, it will likely be mostly sunny and hot in the lowlands and interior valleys. As we work our way up in elevation, weather becomes much more unpredictable, and the cloud forest areas could get persistent to intermittent rain, mist or fog at any time. In the highest elevations, mornings are usually clear and cold and afternoons sunny and cool. Temperatures should stay between 50-90?F for most of the tour; warmer temperatures are possible at the lowest elevations during the first half of the tour. There is also the slim chance of a late cold front, where even in the tropical lowlands low temperatures could drop to the upper 40’s and highs only into the 60’s.

ACCOMMODATIONS: We’ll be staying in hotels and lodges with a wide variety of comfort levels, some excellent and modern. All offer rooms with private bathrooms and hot water showers (usually heated with an electric coil at the shower head). At Refugio Los Volcanes, we will be without telephone but only 45 minutes from the nearest town and a couple of hours from Santa Cruz. Electricity is provided by solar cells and battery there, so while there is lighting in the rooms, there are no electrical outlets; batteries can be charged at the dining room, but electrical appliances such as razors and electric toothbrushes cannot be used. Single occupancy rooms may be available but cannot be guaranteed during the two nights here. All other hotels offer standard amenities, though you may want to bring your own shampoo and washcloth.

Internet and WiFi: There’s no internet in the rural portions of our tour and even in the cities, service is spotty and slow.

FOOD: We will start most days with picnic breakfasts and also have (mostly) picnic lunches in the field. Dinners will usually be in our hotel restaurant and are typically simple meat or fish cuts with sides of steamed vegetables, rice and french fries.

WINGS tours are all-inclusive, and no refunds can be issued for any tour meals participants choose to skip.

Food Allergies / Requirements: We cannot guarantee that all food allergies can be accommodated at every destination. Participants with significant food allergies or special dietary requirements should bring appropriate foods with them for those times when their needs cannot be met. Announced meal times are always approximate depending on how the day unfolds. Participants who need to eat according to a fixed schedule should bring supplemental food. Please contact the WINGS office if you have any questions.

TRANSPORTATION: Our transport will be either minivan, small bus, or a combination of utility vehicles, depending on the size of the group. Participants should be able to sit in any of the vehicle’s seats.

2022 Narrative

With a great group and nearly perfect weather from start to finish, the first of our two Bolivia tours couldn’t have gone much better. We saw and heard nearly 460 species of birds, framed in a wonderful array of habitat types and landscapes. The Olive-crowned Crescentchest that finally showed after our failed attempts at several reluctant birds barely got the most votes as favorite bird, but we worked hard for it, and in the end we were stunned by its beauty and tameness. But a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to watch two male Yungas Manakins displaying for a female was just one point short of a tie with the crescentchest. This rarely seen phenomenon rivals that of the birds-of-paradise, and it seems that this may be the first time a video has ever been made of this species displaying. Ranking farther down the list but still the top birds for some were Black-legged Seriema, Slaty Gnateater, Grass Wren (which may eventually be split at Tucuman Wren), and the endemic Gray-bellied Flowerpiercer. Four other endemics were worth special mention: the fabulous Black-hooded Sunbeam, Red-fronted Macaw, Bolivian Blackbird, and Cochabamba Mountain-Finch. We actually saw four species of tapaculos, but the antics of a Puna Tapaculo on an open branch were especially memorable. A Flavescent Warbler jumped out at us, adorable Tufted Tit-Tyrants came very close, Slender-billed Miners in the highest elevations showed well, a Yungas Pygmy-Owl was just perfect in the mossy branches of the cloud forest, and the sounds made by Crested Oropendolas right by our rooms at Refugio Los Volcanes created an unforgettable atmosphere in addition to the scenic beauty of the place.

IN DETAIL: Our first day around Santa Cruz could have been unbearably hot, or annoyingly windy, but it was neither, instead being calm and relatively cool. And so we were able to bird comfortably through the mid-day hours. Starting at Lomas de Arena with our first of many picnic breakfasts, Greater Thornbirds, Chotoy Spinetail, and Narrow-billed Woodcreeper were our introductions to the family of Furnariids, which we would get to know well. We overlooked a pair of Red-legged Seriemas while being distracted by White-wedged Piculets, a Golden-green Woodpecker, and adorable Cobalt-rumped Parrotlets, but Herman drove us back to where he and Anita had seen them, and they were still there, as were Vermilion Flycatcher and Burrowing Owl. As we departed, a Crested Becard was a very good find, probably a migrant on its way to southern Bolivia or Argentina. After lunch we continued directly to the Santa Cruz Botanical Gardens, now an island of habitat, but still good for birds. In the parking lot we spied two Three-toed Sloths, one with a baby. The Chestnut-fronted Macaws here landed in trees, and we had excellent views of a normally very skulky Great Antshrike and a Hudson’s Black-Tyrant, and it had warmed up just enough for some nice butterfly activity.

Heading south toward the Chaco, we stopped for picnic breakfast in a transition area where the winter had clearly been very dry. A chorus of some seven Tataupa Tinamous during a very brief morning window was the only evidence that we’d have that they even existed. A Southern Beardless-Tyrannulet, part of one small mobbing mix, came in very close, as did a Red-billed Scythebill. We flushed one large group of Red-crested Finches feeding on roadside weeds, and hint that we were getting closer to the Chaco were two Many-colored Chaco-Finches with them, which ended up being the only ones we saw on the tour. We paused on the highway for two Red-legged Seriemas in a field and were lucky to witness their deafening, bugling duet at close range. Another pre-lunch exploration down a side road might have been most interesting for the botanical finds but for a soaring Black-and-white Hawk-Eagle, a very unusual find. After a lunch stop, we looked into a small pond to see some lovely Ringed Teal. A sudden stop for a perched Great Black Hawk was followed by a very close pair of handsome Black-capped Warbling-Finches, which were then followed by an unexpected fly-by of two Military Macaws. We then descended from the highway to check the shores of Tatarenda Lake, where we first flushed a Crane Hawk in the short trees. A Common Gallinule skulked along the edge of the bullrushes where we eventually spotted a female Spectacled Tyrant, probably a migrant heading south. We scanned through flocks of Baird’s Sandpipers, Wilson’s Phalaopes, and Black-necked Stilts, but the rarest bird was the most obvious of all – a lone Andean Flamingo standing out in the distant shallows of the lake. Normally restricted to the high Altiplano, this would represent the first extralimital record of this species anywhere in Bolivia.

Our day in the Chaco east of Boyuibe was delightful. Somehow a cold front had passed without producing rain or even much wind, and the temperatures remained mild all day. A Plumbeous Ibis at breakfast was a nice write-in, and big and noisy flocks of Turquoise-fronted Parrots defined the location. We came across multiple Checkered Woodpeckers, though it was the White-fronted Woodpeckers that made the more lasting impression. Birds with crests were in evidence, with Crested Hornero unusually easy to see, and a pair of Crested Gallitos walking along the shoulder of the road defied their promised skulking nature. A pair of adorable Lark-like Brushrunners finally appeared only when we reached the easternmost point in the road. Another normally shy bird that was super easy to see was a Chaco Earthcreeper that sang at length from a close perch. We pished up several flocks with delightful Stripe-crowned Spinetails, Greater Wagtail-Tyrants, and various tyrant-flycatchers, but Masked Gnatcatchers were always the ones front and center. Black-legged Seriemas are often just a by-product of driving on the road, but we had to work for them this day, eventually getting our best views of one crossing the road in the distance. We were back at the hotel in time for a bit of a break, and flying over the front of the hotel before we headed for dinner in town was a Peregrine Falcon, presumably here for the winter.

We did the entire Lagunillas loop on our fourth day, though the usual vast marshes were said to be mostly dry, thanks to an unusually dry winter following a very poor rainy season. The foothills were indeed exceedingly dry and quiet as well, though we managed to find a trio of Cream-backed Woodpeckers as well as two Lineated Woodpeckers before breakfast. Moss-backed Sparrow was also a nice find, and an Ochre-faced Tody-Flycatcher responded unusually well to playback. At the usual soaring hour, it wasn’t a huge surprise to spot a Short-tailed Hawk or even the three Swallow-tailed Kites, but a total of eight Andean Condors flying down the ridge and then forming a kettle of their own was an amazing sight. We thought we might be seeing even more condors farther down the road, but something wasn’t quite right, and we eventually figured out that an astronomcally high flotilla of huge birds were Southern Screamers, many of which came in to land at what little remaining marsh there was. At lunch the main attraction was the seep of water across the road that harbored several interesting insects, including a Cyna Blue and a pretty little damselfly that has been dubbed the Blue-sided Mountain Coral. Green-cheeked Parakeets came in a large flock to visit the water just as we were leaving our lunch spot. We made a brief stop in the quaint and very quiet town of Lagunillas, and stops north of town netted us White Monjitas and our second White-winged Black-Tyrant on a close fence post. Every seriema we stopped for on this day turned out to be Red-legged, one of the few areas where they occur alongside Black-legged.

Though our next day was largely to be a travel day to our next lodge, we had a wonderful morning of birding at a new location just a few kilometers off the main highway. Thanks to a tip from a birding friend, we arrived at Laguna Kaukaya to have our picnic breakfast where Rosy-billed Pochards were swimming, and many other water birds kept us busy. Coscoroba Swans and “Patagonian” Silvery Grebes are still considered vagrants in Bolivia, but the former obviously bred here this year for the first time, perhaps forced north from drought conditions in Argentina. A rare Spot-flanked Gallinule was distant but eventually seen by all. Purple-throated Euphonias glowed in the morning sun, and Yellow-chinned Spinetails popped out of the marsh vegetation when we asked them to. As we departed the lake, we found two Black-legged Seriemas right next to the road, a nice farewell from the Chaco. Our picnic lunch of leftover mediocre pizza was convenient and quick, but it was also quite productive from a birding perspective, with Streaked Xenops, Yellow-olive Flycatcher, Black-capped Antwren, and Flavescent Warbler (alongside Two-banded Warbler) being excellent additions.

Though we had arrived at Refugio Los Volcanes in the daylight the previous day, the morning’s vista from outside our rooms was still breathtaking and hard to really take in. The noise of flocks of Mitred Parakeets was almost matched by the occasional flyover of Military Macaws, though our best of both were later in the afternoon from the steepest section of a trail, as we looked down on these marvelous birds. A male Crested Oropendola’s song echoed in the valley as his harem of females continuously came and went with nesting material. The previously mentioned Yungas Manakins displaying was a highlight, though we couldn’t have imagined a better morning already having seen a pair of Slaty Gnateaters at arm’s length, a Bolivian Tapaculo perched on a tree’s buttresses, and a Gray-throated Leaftosser that sang from an open perch. Later in the day we watched a pair of fearless Riverbank Warblers in the shallows of the stream, and a mixed flock on the steep trail had Blue-browed Tanager and Orange-headed Tanager, both our only ones on the tour. A surprising find was a Gray Tinamou by the stream’s edge, seen as we were scanning for Sunbittern, which would have been far more likely but remained in absentia. A night walk didn’t result in any owls or potoos, but a Banded Cat-eyed Snake by some army ants was a splendid consolation.

The morning we had to depart Los Volcanes had some nice surprises, with low-elevation Dusky-green Oropendolas in the valley below, a mixed flock with a very close Sepia-capped Flycatcher, and lovely Mitred Parakeets feeding in the trees rather than just blasting by in their noisy flocks. We were ready to depart following an early morning kettle of raptors that included several Plumbeous and Double-toothed Kites as well as two more Black-and-white Hawk-Eagles. After lunch in Samaipata we checked in on a Southern Beardless-Tyrannulet nest woven perfectly in a pendant clump of Spanish Moss bromeliads on the town square. Later in the afternoon we made a planned roadside stretch stop, normally only a few minutes, but it ended up lasting nearly an hour as we had our first Brown-capped Redstart, then heard Bolivian Earthcreeper (which we eventually saw), and were very surprised by a fly-over of eight Red-fronted Macaws, presumably off to a distant roost at the very edge of their known range. On the way to the hotel we had to make a quick pause on the highway to gawk at the unlikely sight of thirty-five Yungas Guans in a vacant corral.

We arrived early at the Perereta macaw cliffs for picnic breakfast, hoping to avoid missing an early morning departure of roosting birds. We soon spotted some distant Red-fronted Macaws on the opposite side of the canyon and had satisfying views of them, but they remained there all morning, and the nearby cliffs were vacant. We had already seen many Cliff Parakeets, Rufous-sided Warbling-Finch, Ringed Warbling-Finch, and endemic Bolivian Blackbirds, but we were just about ready to leave when a small group of macaws flew over our heads from upriver and landed close to where we had been standing for a long time. Herman convinced us they were just arriving, so we walked all the way back and were treated to a wonderful sighting of a family of three birds and super close range. Birding back down the river valley, we stopped for Striped Woodpecker and a nice mix of birds, including Masked Gnatcatcher and White-tipped Plantcutter. On the way to a picnic lunch spot, we paused for a Spot-backed Puffbird with a huge katydid lodged halfway down its throat. At lunch we had great views of White-fronted Woodpecker and a female Blue-tufted Starthroat. A later afternoon stop for our first Andean Gull occurred when we could see the threat of an approaching cold front, and on the shoulder of the road we took the time to watch a scurrying sunspider or solfugid in the oddly named family Mummuciidae, normally found active at night. We had time in the late afternoon to check the lower slopes of the Serrania de Siberia in the growing wind, only hearing a distant Giant Antshrike but getting good views of Ocellated Piculet and a few other birds.

The cold front passed overnight, with wind and rain resulting in a low, heavy overcast that portended fog at the higher elevations. But with rain or wind over by morning, the lower slopes were worth another visit, and we saw lots of fun birds. A pair of Spot-breasted Thornbirds and Yellow-billed Tit-Tyrant were at the first few stops, and we finally spotted the Giant Antshrike. Sometimes sounding only 20 yards away, other times a mile away, then latter guess was more accurate as it popped out in the open but at the top of the ridge of above us – good enough for scope views. Olive-crowned Crescentchests were common and vocal but very uncooperative, until that last one, which appeared just as we needed to head to lunch. Perhaps the higher elevations were fog free? Well, they weren’t but it wasn’t windy, and more importantly it wasn’t super sunny and dead as it can by by mid-day. Instead, birds were very active, and both Red-faced Antpitta and Trilling Tapaculo were vocalizing spontaneously right across from where we chose to make lunch. Amazingly, within minutes both birds were in sight, the tapaculo actually perching on the speaker when we first noticed it. An active mixed flock just down the road had a bold Mountain Wren, Spectacled Redstart, and our first Bolivian Brushfinches, among several others. We tried the higher elevations, but the “backwash” of the cold front led to a big switch in the winds and suddenly we were dealing with a blowing northly gale of mist-fog. Nevertheless, we huddled in the lee of some bushes and spotted at very close range our first Black-throated Thistletail, a special endemic of the highest treeline scrub.

The start to our day on the long drive to Cochabamba didn’t look so auspicious. It looked as if the cold front was still holding sway, and while the lower curves were visited by an occasional, mist, we passed by our antpitta and tapaculo spot in dense morning fog. But as we reached the highest elevations, we broke above the fog and found a stunning sunrise above a blanket of fog below us and expanses of treeline cloud forest on a calm and chilly morning. White-browed Conebills were right by our breakfast pullout as was a pair of “Tucuman” Grass Wrens on top of the grassy knoll nearby. We walked back down the road to hear mostly distant tapaculos of both kinds, Trilling and Diademed, finally finding a bamboo-filled draw where the latter came down close to the speaker. Two singing Undulated Anpittas sounded as if they should be visible, but the only other good bird we managed to see here was the Yungas Pygmy-Owl, a very good bid indeed, and we saw it well. Not far down the road we stopped in a slightly drier cloud forest, and as we stepped out of the bus a bunch of new birds greeted us, including the very local and scarce Rufous-bellied Mountain-Tanager (formerly Salator) and the endemic Gray-bellied Flowerpiercer. An endemic Bolivian Antpitta calling up the slope seemed hopelessly far across the draw, but magically it came all the way to the speaker and we saw it very well. We had picnic lunch where Pale-footed Swallows flew over the cloud forest and a Pale-legged Warbler came in very close. Another couple of stretching stops were good for Red-tailed Comet, White-browed Chat-Tyrant, and Giant Hummingbird.

Fabulous weather greeted us again for our day birding the mid- to upper-elevation cloud forests of the Chapare Road. Before we even arrived at our breakfast spot we had to make a stop for a burst of activity right on the highway, where several Andean Guans, a flock of Green Jays, and a pair of Three-banded Warblers distracted us. We noted how different the songs of these warblers were compared to birds from central Peru northward, commenting how they will eventually be split. Just a month later that came true, and these birds are now known as Yungas Warblers. We ended up having breakfast and lunch at the same location, and it was consistently the birdiest spot on the road. We did get our best views of near-endemic Yungas Tody-Tyrant farther down the road, but at the picnic spot we had Crested Quetzal, Deep-blue Flowerpiercer, and Green-throated Tanager, among many others. Butterfly activity was excellent here as well, and a light-blue, almost holographic morpho was especially memorable (which turned out to be the Aurora Morpho). We birded the afternoon at higher elevations, trying to beat the approaching fog. We caught up with a very skulky Golden-browed Chat-Tyrant; were teased by a mixed flock that had Scarlet-bellied Mountain-Tanager, Citrine Warbler, and Rust-and-yellow Tanager, and a few others; and finally came across a very obliging pair of Hooded Mountain-Toucans, accompanied by White-collared Jays. One final memorable bird from the day was the Great Kiskadee of the unusual, pale subspecies endemic to the Cochabamba area, at our gas station stop in Colomi.

We spent our last full day up the Cerro Tunari road, enjoying a slightly later departure than usual, as it is very close to Cochabamba. Getting there early was good, as we surprised an Andean Tinamou walking out in the open, our only second seen tinamou. We stopped for a flurry of parakeet activity to find not only the common Gray-hooded Parakeet but also the much more rarely seen Andean Parakeets. Another pocket of activity contained our only Cochabamba Mountain-Finches, a pair that came in very close, while at the same spot were adorable Tufted Tit-Tyrant, Rock Earthcreeper, and our first of a few Gray-bellied Flowerpiercers. Not far up the road we stopped for a flock of Greenish Yellow-Finches, and as the habitat looked right, we brought in a Maquis Canastero – our first of five species of canasteros this day, perhaps the only road in the world where this is possible. Near our lunch spot was a pair of adorable Tawny Tit-Spinetails and a cheeky Puna Tapaculo that sang at length from an open branch. Then it came time to head to the higher elevations, quick stops netting us Puna and Scribble-tailed Canasteros before we embarked on a pleasant walk in a broad valley to look for Boulder Finch. They did not cooperate, but we were instead treated to a large flock of lovely Bright-rumped Yellow-Finches, as well as several migrant White-browed Ground-Tyrants and resident Taczanowski’s Ground-Tyrants. We finished the day with a jot up to the highest point on the road, which looked at first to be birdless but in reality was home to a Cordilleran Canastero and a pair of smart Slender-billed Miners. A quick check of the small lake near the top yielded Crested Duck, Puna Ibis, and a rather out-of-place Stilt Sandpiper, while the grassy flats had a few more ground-tyrants, including Cinereous and Ochre-naped.

We finished the tour with a final early morning at the treeline scrub amidst potato fields. We arrived just as Red-crested Cotingas were finishing their dawn displays with their crazy crests all flared out. When they disappeared, we concentrated on some mixed flock activity as the fog came and went, finding White-browed Conebill and Scarlet-bellied Mountain Tanager, while Black-chinned Thistletail and Bolivian Brushfinch foraged in the bushes right where Herman and Anita prepared our delicious breakfast. We soon found our main target, a stunning Black-hooded Sunbeam, defending its Mutisia lanata flowers nearby, but a walk up the road would net us a total of about nine individuals, as well as a huge Great Sapphirewing feeding from terrestrial Puya bromeliads. We heard both endemic Rufous-faced and Bolivian Antpittas nearby, but since we had already seen them so well, we concentrated on a third antpitta – Undulated Antpitta – that was even closer. We never quite saw the thing perched, but we were all prepared for the second time that it flew across the track, a monster of an antpitta. Our last special bird here was a pair of Line-fronted Canasteros, our seventh canastero, and a species with very records this far south. Our last bit of birding after lunch was a stop at Laguna Alalay, where we scanned through many migrant sandpipers, local Black-necked Stilts, Andean Avocets, and a single Collared Plover to also spy Plumbeous Rail and a pair of Red Shovelers. We arrived with some time to spare at the airport, bid farewell to both Peter and Anita, and flew to La Paz for the second tour.

-Rich Hoyer

The single occupancy supplement indicated above covers only those sites where single lodging is available. Please note that single occupancy will not be available at Refugio Los Volcanes.

Maximum group size eight with one leader.