From the Field

June 16:

Paul French on his Feb-Mar 2020 tour to Senegal

It's been many years since we did a Senegal tour, and much has changed in the interim. A increase in both local and visiting birders has really highlighted the enormous potential of this relatively small West African country, and its position straddling the Saharan, Sahelian, Sudanese and Guinean biomes makes for a fascinating birding adventure, with a couple of specialities and several species that are difficult if not virtually impossible to find elsewhere. Here are a few images from the tour.

Moving north from Dakar, we were soon into open savannah woodland, and one of the immediate highlights of the tour was this mixed group of vultures on a carcass. Ruppell's Griffons and African White-backed were most numerous, but there were also several Eurasian Griffons and a couple of hulking Lappet-faced Vultures.

The acacias and scrub in the north of Senegal are home to several of the specialities. One of the easier ones to find is Cricket Longtail, a demonstrative and striking bird, its calls and song carry a surprising way.

One of the biggest revelations in recent times has been the regularity with which Golden Nightjars can be found at day roost. Such beautiful nightjars, but so incredibly difficult to find at roost!

Another of the charismatic birds is the Black Scrub Robin, a proper little charmer! Pleasantly common and even present in our hotel grounds.

From the Sahel zone we moved a short distance into one of West Africa's premier wetlands, the Djoudj National Park. This area of seasonally flooded wetlands is home to huge numbers of waterbirds, here are clouds of White-faced and Fulvous Whistling Ducks, plus a striking pink line of Greater Flamingos.

Also here in good numbers is the recently identified African Golden Wolf, not quite as sturdy as its northern cousins but still a beautiful canid.

Moving south into the Senegal heartlands, the low bushlands near Kaolack hold one of the most sought after birds of the tour, the enigmatic Quail-plover. Now thought to be an aberrant button-quail, this odd species has a huge distribution from Senegal to Kenya, but is incredibly hard to find. This is now by far the most reliable area in the world for them, and we enjoyed "walk-away views" of one as it sat under a bush, and then flushed and we experienced the remarkable wing pattern.

Nearby is the famous Scissor-tailed Kite roost, hosting several thousand birds at its peak in mid-winter. Truly one of the most elegant and beautiful of raptors.

Moving SE, we spent three nights at the excellent Wassadou camp, situated on the Gambia River. The birding here is great, and as well as walking from the camp through the scrub and open woods, we also take a boat trip down stream to get up close and personal with some of the species found here..

..such as the incomparable Egyptian Plover.

The bee-eater colonies along the river are always popular, and seeing flocks of Northern Carmine Bee-eaters hanging off bushes like gaudy Christmas decorations always lifts the soul.

Alongside the Carmines, these Red-throated Bee-eaters are just as attractive, and while they may not have the size and long tails of their neighbours, those blue undertail coverts are a stunning feature in their repertoire.

The Blue-breasted Kingfisher is pleasingly easy to see here

Our final destination was the dry woodlands and rocky escarpments of the Kedougou area in the far SE of Senegal. Here there are several more specialities, and we succeeded with them all. One of the main targets is the Mali Firefinch. We struck gold with this species, after this pair on our first evening, we found a spot with up to 40 birds coming to drink, plus a pair of Neumann's Starlings. While a bit distant for photos, 'scope views were more than good enough.

Overhead, we always keep one eye on the raptors, and this striking Beaudouin's Snake Eagle was one such reward.

June 10:

Susan Myers on her local Cooper's Hawks

Although I’d rather be out working, it’s definitely been rewarding getting out every morning and studying/photographing local birds. The Cooper’s Hawks are gearing up for the arrival of their chicks and I’ve been following progress and documenting their fascinating activities. I’ve been observing three pairs with nests here in Seattle. The nest building began about three weeks ago and the location of one of the nests allowed me to closely follow the collection of the twigs and branches used in construction. The work was shared but the female seemed to be the supervisor, while the male, maybe being a bit inexperienced, behaved a bit like the class clown.

The larger female was more skilled at choosing and transporting branches; she appeared to pick a suitable branch in advance, then fly in to break it off and bring it back to the nest located in a small stand of poplar trees.

The male however was more active and mobile during most of my sessions watching them.

And how do I know which was the female and which was the male? This is how:

A couple of weeks down the track, and the female of all pairs on the nests I’m watching seem to be incubating. It’s hard to be sure that they’re all still active as the female is often not visible on the nest. I do know that one pair are so far successful, as I watched the male hunting close to the nest, jumping onto the ground from low branches and presumably searching for small rodents or the like.

So, even though this time of Covid sometimes makes me feel like this:

I’m not too unhappy as long as I can get outside with the birds!

May 27:

Stephen Menzie from his non-birdtour life...at a bird observatory,

It’s been a spring of changes for me, and not just for the obvious reasons. In early March, I moved from the UK to southern Sweden where I began work as the new manager of Falsterbo Bird Observatory. It’s an area I know well, having worked here as a bander in the past and, indeed, leading the WINGS fall tour – but, nonetheless, a permanent move abroad is always a much bigger step than three months here and there. My flight in landed in Copenhagen, Denmark, before I took the short journey across the Oresund bridge into Sweden. I was lucky. Very lucky. Had I arrived a week later, I wouldn’t have been able to cross the border.

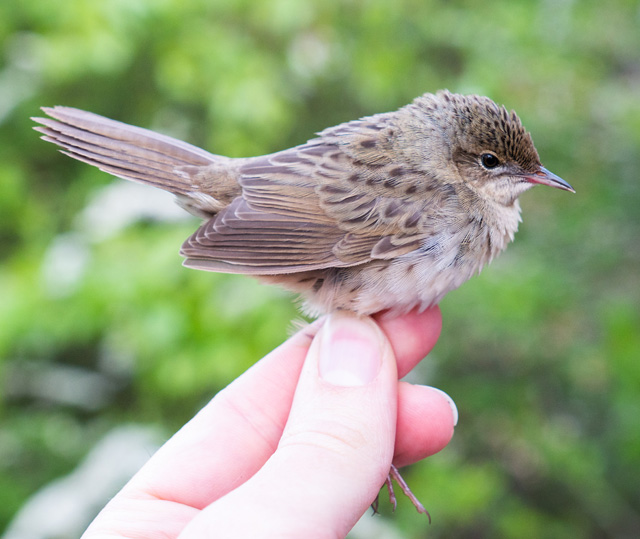

It’s been well publicized that Sweden has taken a rather relaxed approach to the current global situation. Friends in Stockholm would beg to differ that the situation up there is far from normal – Swedes are good at social distancing, even without government enforcement; but, down here, away from the cities, life is, by and large, carrying on as normal. At least it is at the observatory. There are just a few of us working and living here and every morning is spent banding birds as part of the observatories 41-year systematic monitoring of migrant passerines.

2020 has been a fairly average spring – although average in Falsterbo means over 3,000 birds banded so far.

The bulk of these have been European Robins, above, and Willow Warblers.

Niceties amongst the usual fare has included a Ring Ouzel, a Grasshopper Warbler, both above, and an above-average number of Common Redstarts.

Of course, walking the net rounds all morning inevitably results in some birding, and notable sightings whilst ‘working’ having included a Eurasian Green Woodpecker, several Wrynecks, both above, a young female Hen Harrier, flocks of Western Yellow Wagtails (including many of the dark-headed subspecies thunbergi, above), White Wagtails, and Eurasian Sparrowhawks.

It’s not just birds that have been the focus of my photographic attempts. The small windmill outside the bird observatory building – which will look familiar to anyone who has been on my Falsterbo tour; it’s a great raptor watching spot! – has provide photo inspiration day and night, above.

Mid-May is two-thirds of the way through the spring season, but it’s just about now when we start to see some of the really exciting summer migrants arriving. Species such as Red-backed Shrike, which should be with us any day now. They’re one of those species that’s a joy to see at such close range but a nightmare to handle. Their nickname of ‘butcher bird’ is well deserved. Watch this space for further updates including photos of Red-backed Shrikes and butchered bander’s fingers…

May 18:

Jake Mohlmann on how he fills in his cancelled-tour time

I have been fortunate enough to have my other occupation both flexible to some degree and deemed essential by the states of California and Nevada where I work as a biologist surveying and monitoring threatened and endangered species. Near Desert Center California I spent a week monitoring several Desert Kit Fox dens to see how the families were progressing this season. In the early spring families of foxes are having pups and tend to be more approachable than usual.

A young Desert Kit Fox pup emerges with mom nearby.

Most of my research this spring has been with the endangered Mojave Desert Tortoise, hoping to confirm that populations of this reptile remain healthy.

Inspecting a Desert Tortoise for distinguishing features.

Taking measurements on an adult tortoise.

While traversing the seemingly endless desert there's never a time I stop birding. Despite the reputation of the desert being deserted, wildlife thrives in this region with beautiful annual flower blooms, huge migrating flocks of birds, and sometimes rare denizens like nesting raptors. Occasionally I'll flush a roosting owl in the large washes meandering through the landscape, like the other day when a Long-eared Owl was just as surprised to see me as I was to see it turned out to be the bird that flushed from an Ironwood Tree at close range.

Long-eared Owl breeds in the desert southwest

May 15:

Fabrice Schmitt on his quarantine in France

Two months locked down at home during spring migration! The last time I can remember anything as painful was quite a few years ago when I made a much anticipated vist to a restricted wetland filled with waders... and I realized I'd forgotten my binoculars and telescope! At least I now have time to edit most of my pictures and some of my sound recordings (although I still have enough of these for Covid-20, 21, and 22, at least).

Luckily, after five weeks with my nose glued to my apartment window and my eyes scanning the sky for migrants, I am now participating in professional bird inventories in Lozère (South of France). This gives me a legal way to get outside, and enjoy at least the tail end of the spring migration. One of the places I am monitoring is filled with breeding Northern Wheatears and Meadow Pipits, and a male Whinchat was still waiting for his female during my last visit.

Northern Wheatear

Whinchat

Spring is delayed at this high-altitude location and the splendid Pulsatilla rubra are still in bloom, and Viviparous Lizards are just starting to warm during sunny days after their long hibernation.

Pulsatilla rubra

Viviparous Lizard

On the way to the study area I sometimes spot recently-arrived migrants, such as Golden Oriole, Western Bonelli’s Warbler or European Cuckoo.

Golden Oriole

Western Bonelli's Warbler

Stay safe and hopefully the fall migration will be more convivial!

May 10:

Steve Howell on the Local Bigfoot Year, not by choice in 2020

The idea of a Big Year has become part of today’s birding culture: “How many species can I encounter in a year?” Some people cover the whole of North America, others a state or province, others a county, a few even the world—it can be done at any scale, although 2020 would have been a bad year to pick for almost any area. The exception being around your home. For better or worse the previous two years have prepared me for an unplanned year of very local birding.

Back in 2018, as things moved into February I wondered if I could find 200 species in the year just on foot around town, here on the coast of central California. To put 200 species in perspective (after all, one could find 200 species in a morning in eastern Ecuador!), a decent county year list is in the order of 260 to 280 species. So this seemed a plausible, but not necessarily easy goal. Plus I threw in two more criteria—no scope and no chased birds. I didn’t plan any long hikes, just walked in and around town, which translated into birding within a 1.5 mile radius of my home. So how did it work out?

Well, I learned a lot about the local birds and got to know many of the local humans, even showing one person a roosting Northern Saw-whet Owl, another a roosting Barn Owl, and being given invites onto private property.

My first species for 2018 was Wrentit, heard from bed on New Year’s morning.

This roosting Barn Owl was in a tree on the corner of my block, just for one day but appreciated by a passing cyclist.

Whereas this Northern Saw-whet Owl stuck around for a week or so, helping keep down the local mouse population.

The 2018 Bigfoot Year also confirmed that time in the field is the number one factor for finding rare birds: I saw what most people would consider a ‘rare bird’ for only about one minute in about every 30 or 40 hours of birding—a pretty low return put that way, but fortunately it wasn’t about rare birds. Purely by chance, though, 2018 turned out to be a really ‘good year' for vagrants in central California, and I hit 200 species by noon on October 1st (a Baltimore Oriole, only my second in the county). Well, that was easy, and by the end of the year I reached 218 species, which had a nice ring to it—218 in 2018.

In the next post I’ll summarize my 2019 Bigfoot Year (hey, don’t worry, for better or worse we’ve got time ;-), and then bring you up to date with Bigfoot 2020, in progress. Meanwhile, here are some photo highlights from 2018.

I recommend a Bigfoot Year to anyone, anywhere, if you have the time and inclination—and in 2020 it seems we have the time... Even a Bigfoot month. You only compete against yourself and the birds, and learn a lot along the way. Depending on where you live, your Bigfoot Year goal might be 50 species, or 123 (no reason it has to be a round number!), or if you live in Amazonia, maybe 400 species. And it’s a lot cheaper than chasing around a country or even a county. Lastly, a big thanks to local birders Keith Hansen, Catherine Hickey, Mark Dettling, and Diana Humple for their company from time to time, even though all of them saw at least one species I missed for the 2018 Bigfoot Year!

This young male Broad-billed Hummingbird was ‘downtown’ (just over a mile away) at Keith Hansen’s feeders, but because I wasn’t chasing birds in my Bigfoot Year I waited 3 days before I was going down to the store, when I always stop in and visit Keith’s feeders next door—fortunately the bird stuck around, and it sure stood out among the local Anna’s Hummingbirds.

OK, I know I like molt, but when I found this bird on 8 October (here) it was molting so heavily it was a challenge to even identify—a Painted Bunting on some private property a few blocks from my home, and ‘officially’ the rarest bird of the year. I was able to follow its molt for a month and it turned out to be a normal preformative (‘post-juvenile’) molt both in timing and extent—that is, almost complete, just retaining some inner primaries, outer secondaries, and primary coverts. It was simply undertaken in the wrong place.

On 15 October, the tail starting to grow...

On 23 October, tail mostly grown, outer primaries still growing...

On 7 November, finished and the last date I saw it, and hopefully it headed off to Mexico.

‘Unofficially’ the rarest bird of the year (for me) was this pseudo Broad-tailed Hummingbird, a male Anna’s xSelasphorus hybrid a few blocks from home on 10 July.

May 8:

News from Rich Hoyer, happily riding things out at home.

I was actually planning on being home for most of April and May anyway, looking forward to spending time in my new home and yard. I have plans on making my residential Eugene garden more friendly for wildlife, as well as preparing for a summer of growing as much of my own food as possible – even before I knew I might be spending the rest of the year at home and needing to lower my monthly food bill. I’m already well on my way to having a full freezer and pantry of canned food this coming fall, barring any catastrophes.

The previous owners had already planted fruit trees and berries as well as lot of perennials beneficial to our many species of native pollinators. There were several clumps of sunchokes, doubling as food native bees and humans, and one clump offered up 25 pounds of roots this winter. But with the warmer spring weather, they were starting to sprout, so I quickly put 3 pounds of them up as pickles.

I added several nest boxes, a bat box, and have sunk over 50 native plants into what used to be lawn and will someday be something resembling a native brushy prairie.

It was exciting to see the first returning Violet-green Swallows in early March and even more exciting to see that a pair has exhibited great interest in one of the boxes I made and put on the east side of the house in the past week. I find that its beauty rivals that of any other swallow in the world.

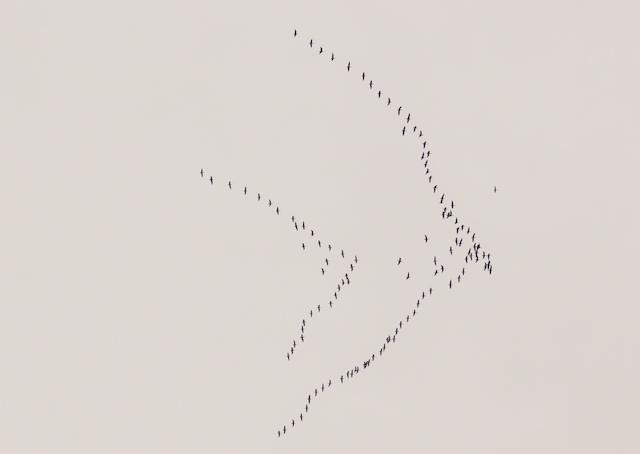

I also planned ahead to be home during the exciting time of spring migration, building up my new yard list. I’m adding birds almost daily. Flocks of Greater White-fronted Geese en route from their staging area in the Klamath Basin to Alaska flew right over my yard starting on April 19, becoming species number 90 on the list.

Four days later a most obliging Dusky Flycatcher, a rare migrant in western Oregon graced my and my neighbor’s yard, becoming number 95. 100 is well within sight.

May 6:

Paul Holt on his lockdown activities in the U.K.

Following tours to Myanmar and North India I couldn't get back to China and ended up, reluctantly, returning to the UK where I remain. Three months on from when I left Qingyu, my partner and the ‘fixer’ for all of our myriad China tours, is still under lock down in our apartment in Beijing. Very local birding in East Lancashire has given me a chance to reacquaint myself with many of the common birds of my youth (and has brought home exactly why I left!) In between various chores I've been busy sound recording several commoner species in the garden. A few of my recordings, nearly identical to the thousands of others already on the internet, can be listened to at –

Common Blackbird https://www.xeno-canto.org/544271

Song Thrush https://www.xeno-canto.org/546323

European Robin https://www.xeno-canto.org/546325

Mistle Thrush https://www.xeno-canto.org/546314

Eurasian Blackcap https://www.xeno-canto.org/546304

Rook https://www.xeno-canto.org/546319

That’s all for the moment. You really wouldn’t want a photo of me right now – I’ve not been anywhere near a barber since mid-January and look positively Neanderthal-ish.

(Editor's note: Paul may be right that there are thousands of internet recordings of the above species but there aren't many of this quality. If you have time for only one, try the Eurasian Blackcap.)

May 4:

Susan Myers on her at home photo explorations of Anna's Hummingbird.

In lieu of leading my tour in the Philippines, I decided I would just stay put and go photograph Anna’s Hummingbirds… Well, this might not be an entirely true representation of my personal recent history, I have to say that local birding in Seattle has been rewarding and fun, if rather lonely. One of my projects that I’ve set for myself is to improve on my photography skills - slow down and spend the time, work on techniques and wait for the bird to show some interesting behaviour. Anna’s Hummingbird is a common garden bird all along the west coast but it’s always a challenge to photograph them. I’ve been lucky to find a perfect model - I made the acquaintance of this male Anna’s last year and was delighted to find him back in exactly the same place this year. I’ve now spent many hours in his company, so here I present the many moods of an Anna’s Hummingbird in spring.

April 27:

Luke Seitz on quarantining in Maine.

April showers bring May flowers, or something like that? The past few weeks (days? months?) of quarantine/time-warp here in Maine have not felt very spring-like, although April always holds a few surprises. Pictured here is a friendly Prothonotary Warbler that showed up in a small park in Portland, viewed while wearing a face-mask and standing at least six feet away from other birders!

He seemed unconcerned about germs and droplets as he foraged along the edge of a pond, coming far too close to focus…

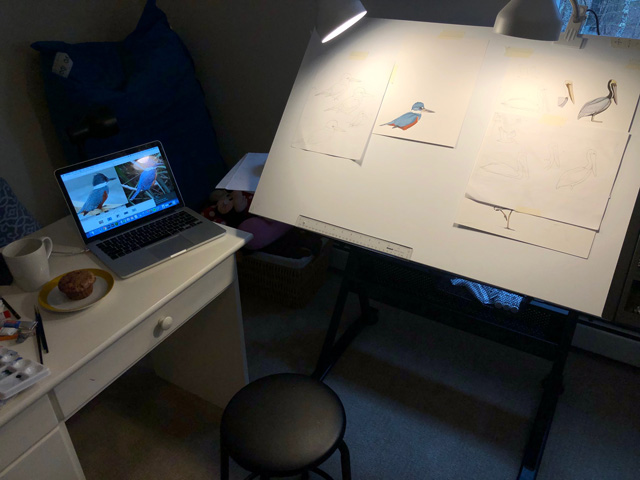

But most importantly, being stuck at home has been a good excuse to work on illustrations for an upcoming field guide to the birds of the Caribbean. I’m a very slow painter so feelings of progress or accomplishment are hard to come by, but there’s no better way to do it than just…sitting down and painting all day, every day, right?! Here’s the setup, including a few partially-finished plates and complete with delicious homemade raspberry muffin.